In honor of February being Hawaiian Language Month, Mahina ‘Ōlelo Hawai’i, I present here some information about the Hawaiian language that visitors may be unaware of. These are things I’ve learned as a student of the language, in the course of my linguistic research, and through my nearly twenty-years traveling to and living in the islands. Please note that I am writing this from the perspective of a non-Hawaiian (linguist) for non-Hawaiian visitors. Given that ‘Ōlelo Hawai’i is not my language and does not belong to me I am currently planning a follow up that will incorporate the kānaka maoli voice; i.e., what Hawaiians want visitors to know about their language.

#1: The Hawaiian language is endangered but NOT extinct.

Some visitors assume the Hawaiian language (ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi) has met the same fate as other indigenous languages in the face of imperialist expansion; i.e., extinction. However, this is not true. In fact, Hawaiian is all around you when you come to the islands, both in written and spoken form. While it is obvious in its presence on street signs, ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (ʻŌH) is also taught in most schools, and spoken at home and in public. In fact, according to the State of Hawaii Data Book for 2022, ʻŌH is spoken at home by 25,800 individuals. This makes ʻŌH the sixth most non-English language spoken at home, after Ilocano, Tagalog, Japanese, Chinese, and Spanish. ʻŌH is also an official state language, though the extent to which this is implemented on the ground varies (Honolulu Civil Beat). While ʻŌH did go through a period of decline due to events discussed below, it appears to be stable, thanks to the revitalization movement.

#2: ʻŌH was suppressed and its speakers marginalized after the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, leading to its decline.

The Hawaiian Kingdom was an independent nation until 1893, when a cabal of local businessmen initiated a coup, with the backing of the United States military.1 The true goal of many of the coup leaders was for Hawaiʻi to become part of the United States; i.e., annexation. However, that would not occur until 1900, when it became a US territory. In the meantime, the provisional government, which styled itself the “Republic of Hawaiʻi,” took measures to make Hawaiʻi more tempting to the United States for annexation. This affected ʻŌH in the form of Act 57, which made English the only language allowed for instruction in both public and private schools, effectively turning ʻŌH into a second-class language. Students were not allowed to speak it at school and it lost its previous status as the de facto prestige language of the islands. This negative stigma ended up in Hawaiian homes where the language was no longer passed on, so that future generations would not suffer the same types of punishment their parents suffered in school.

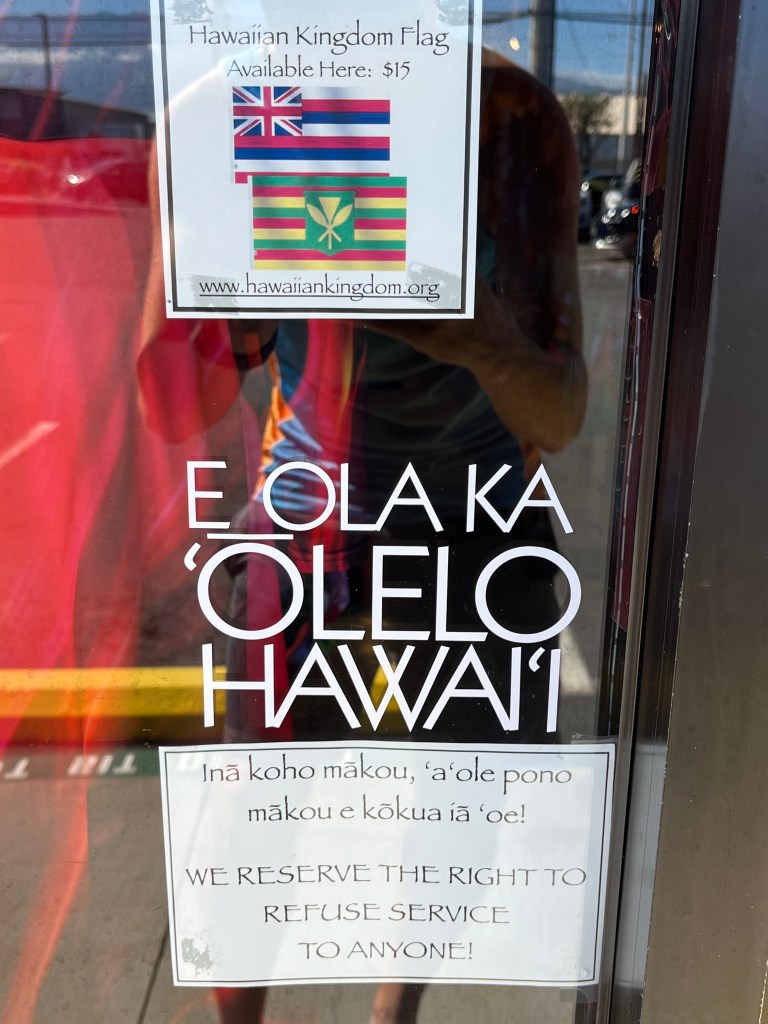

After a period of obsolescence, we can fast forward to the 1970s, when Hawaiians started to reassert their identity during the Second Hawaiian Renaissance. In the 1980s, many elder native speakers of ʻŌH (kūpuna) were passing away, which meant the language would disappear with them if countermeasures were not taken. This is when the Hawaiian Language Revitalization Movement developed, leading to the establishment of ʻŌH immersion schools. For more details see NeSmith (2005) and references therein. The main take away here for visitors to Hawaiʻi is that learning and propagating the language is part of a greater movement among Hawaiians to maintain their identity. Hawaiians are proud of their language! The revitalization and language-maintenance process is ongoing and visitors should do what they can to help support it.

#3: The Hawaiian language is NOT just a spoken language, with little to no literary tradition.

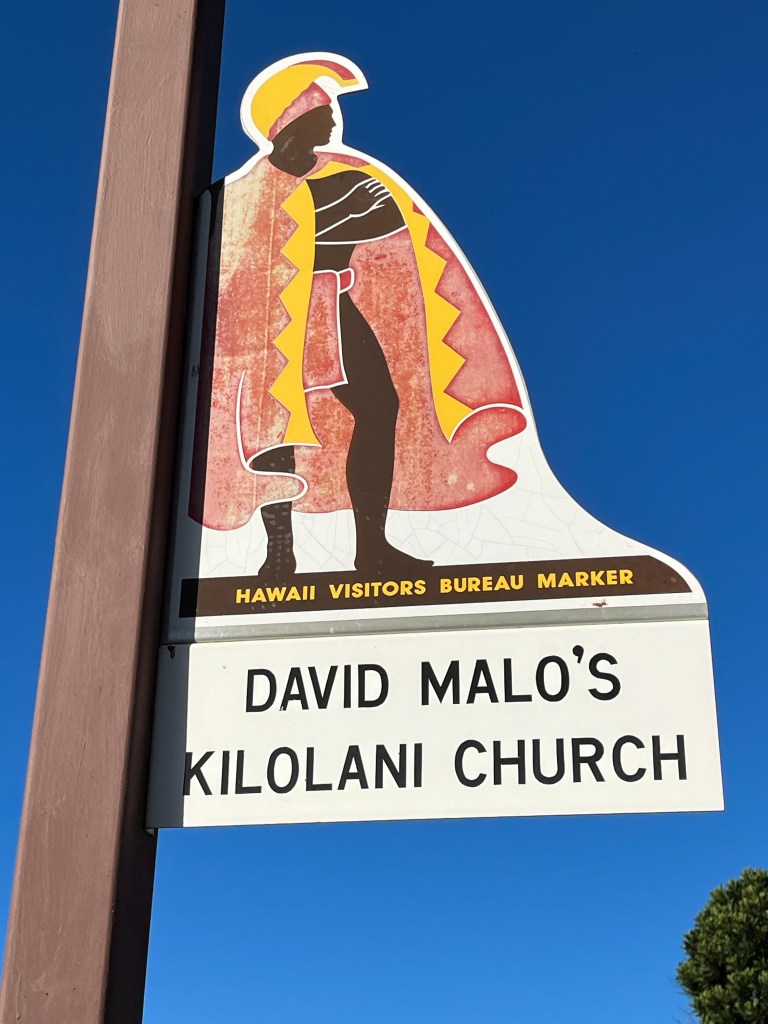

First of all, it is a common myth that languages that are not written down are “primitive” or “backward.” I return to this point in #4 below. As for ʻŌH, while it is true that it had no alphabet or textual culture prior to the arrival of the Protestant missionaries in 1820, once the tools were developed for it, Hawaiians were quick to learn, resulting in Hawaiʻi having one of the highest literacy rates in the world at the time (91-95% according to Kukahiko et al 2020). One of the texts first produced in ʻŌH was, of course, a translation of the Bible, Ka Baibala Hemolele, which was the joint effort of New England missionaries aided greatly by native speakers like David Malo, a very influential and early writer in ʻŌH.2 This Bible text is still read aloud in Hawaiian church services like the one I recently attended in Kihei, in the church founded by Malo himself, Trinity Episcopal By-the-Sea.

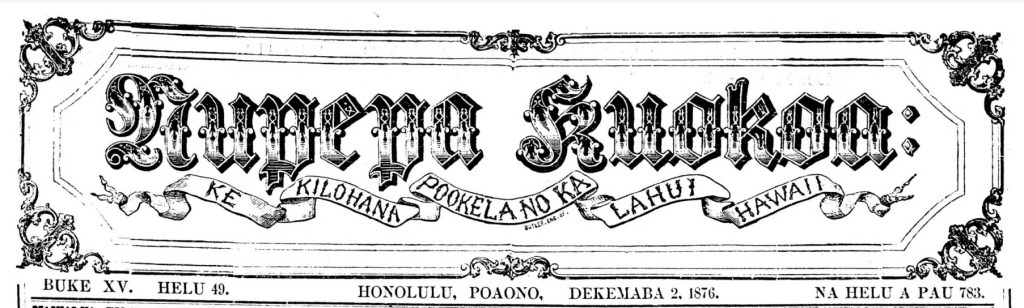

Another ʻŌH literary tradition is represented by the abundance of newspapers published in the language during the 19th and 20th centuries. Fortunately, much of these have been preserved and even digitized, and are available online via the Papakilo database. The history and influence of the newspaper tradition is studied in detail in Chapin (1996).

ʻŌH continues to be part of the periodical culture of the islands, as evidenced by the magazine Flux: The current of Hawaiʻi, which regularly features full length articles written entirely in ʻŌH (shoutout to N. Ha’alilio Solomon, Flux’s ‘ŌH editor).

#4: ʻŌH is not more “primitive” or “simpler” when compared to western languages.

This is another myth that non-linguists might have acquired as a result of western education. No serious linguist these days would claim that any language is more complex than the other. There are various problems with this idea, the most obvious being how to measure the level of complexity. How does one even define “complexity” here? If a language has more consonants than another, does that mean it’s more complex or sophisticated? No. In fact, ʻŌH has the same amount of vowels (five “long”, five “short”) as Classical Latin. So if we’re using vocalic inventory as a metric, at least with respect to vowels, we’ll have to place Cicero and David Malo on the same level.

I know what some of you former Latin and Greek students may be thinking: “Okay, but what about the declensions! And the conjugations! Does Hawaiian have that?!?” I know as students it was ingrained into us that a sophisticated language should be characterized by an overabundance of declensions to memorize. It is true that ʻŌH does not have this kind of rich morphology (fortunately for students of ʻŌH). However, again, this is an idea inherited in western society as a legacy of the classical and humanistic tradition. By the way, English has little to no nominal declension or verbal conjugation either, and yet we have all had to suffer through an English professor’s lectures on the ineffable eloquence of various British and American authors. However, while no one would claim that Shakespeare was not eloquent, this is a matter of writing style, not language. Shakespeare’s actual English was not more complex than any other language, including ʻŌH.

#5: Hawaiians appreciate it when visitors respect their language.

Have you ever had anyone mispronounce your name? If you’re of Anglo-American heritage and haven’t gotten out much, then maybe not. However, if you’ve ever been on the receiving end of this, it can be annoying if not offensive. And those of minoritized backgrounds usually suffer this the most. Even I have had this happen on more than one occasion. I once had a professor refer to me as Mr. Mad-doze. He must have wanted to treat the <x> in Maddox like the one in xylophone, which makes some sense by means of analogy, but in my family we have always pronounced it like Mad-docks.

Now imagine you’re part of a community whose home was taken over and culture and language suppressed. Wouldn’t you be irked if an outsider mangled the pronunciation of your hometown or your name? This is why it is important for visitors to learn to pronounce ʻŌH places and proper names more accurately. The good news is that ʻŌH is a highly phonetic language, by which I mean that each letter corresponds to roughly one sound, much like Spanish but much unlike French or English. Compare the following:

(1) February (English)

(2) Febrero (Spanish)

(3) Pepeluali (Hawaiian)

For English (1), I guarantee you’ve heard several different renditions. Is it ‘feb-roo-ary’ or ‘feb-yoo-ary?3‘ I think in the UK they say something like ‘Feb-ry’. How you pronounce it likely depends on your geographic origin and/or socioeconomic background. However, for (2), there is much less variation even though Spanish is spoken by something like 600 million people around the world. The worst I’ve heard a student do with (2) is pronounce the <r> like an English <r>, which is understandable when learning the language. Now consider (3). It’s pronounced almost exactly as written: pe-pe-loo-ah-lee. This is actually a loanword, but it still illustrates the point that ʻŌH is not as hard to pronounce as some might think.

Here are some common repeat offenders that tend to get butchered by visitors and even long-term transplants: Kāʻanapali, Lanaʻi, Molokaʻi. Most of the errors have to do with the ʻokina (ʻ), which is an actual consonant, not a diacritic or accent mark. The ʻokina is technically a glottal stop and even if you can’t produce it yourself, just keep in mind that it also separates syllables. That’s why Hawaiʻi is pronounced with three syllables: Ha-wai-ee, NOT Ha-wai. Now extend this to the other examples: La-nah-ee, NOT la-nai (which is another word but not the name of the island); Mo-lo-kah-ee, NOT Mo-lo-kai. Making this adjustment is a simple but effective way to respect the language and by extension the Hawaiian people.

Before concluding, one more example must be mentioned. If you ever find yourself on the north shore of Maui, around Pāʻia (another commonly misprononced town), you may end up at Hali’imaile, which has a nice general store/restaurant that I definitely recommend trying out. Unfortunately, the name of the village tends to cause difficulty, again in part because of the ʻokina. Haliʻimaile is pronounced: Hah-lee-ee-my-leh, NOT hiley-miley. I’m not sure why but this particular mispronunciation annoys me more than others.

Pronunciation aids are easy to come by. Look at any ABC Store and you’ll find basic Hawaiian phrasebooks that usually have a pronunciation guide. Also, the book, Island Wisdom, by Native Hawaiian and cultural advisor Kainoa Daines and Annie Daly has a basic intro for lay people, in the chapter on mo’olelo (stories). This book also has a ton of other useful cultural and historical information for non-Hawaiians. Another strategy to help with your pronunciation is to watch the local news while on island. The news reporters almost always pronounce place names and proper names correctly, probably because it’s network policy. Just listen and repeat.

And there you have five things to know about the Hawaiian language if you plan on visiting soon. Naturally, this list is not exclusive and there is much more to be said, but I’ll leave that for future posts. Also, respectful and insightful comments are welcomed. Aloha and safe travels!

References

Chapin, Helen Geracimos. 1996. Shaping history: The role of newspapers in Hawaiʻi. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press

Daines, Kainoa and Annie Daly. 2022. Island Wisdom: Hawaiian traditions and practices for a meaningful life. San Francisco: Chronicle Prism.

Daws, Gavan. 1968. Shoal of time: A history of the Hawaiian islands. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Kukahiko, Kealiʻi, Pono Fernandez, Dawn Kauʻi Sang, Kamuela Yim, Anela Iwane, Kaʻanohiokalā Kalama-Macomber, Kuʻulei Makua, Karen Nakasone, Dana Tanigawa, Kāhea Kim, Leināʻala Cosma Reyes and Tristan Fleming-Nazara. 2020. Pūpūkahi i Holomua: A story of Hawaiian education and a theory of change. Encounters in Theory and History of Education 21: 175-212.

Lyon, Jeffrey. 2017. No ka Baibala Hemolele: The making of the Hawaiian Bible. Palapala 1:113-151.

NeSmith, R. Keao. 2005. Tūtū’s Hawaiian and the emergence of a neo Hawaiian language. ʻŌiwi Journal-A Native Hawaiian Journal. Honolulu: Kuleana ʻŌiwi Press.

Some informative videos from PBS Hawaiʻi:

What Role Does Hawaiian Language Play in Our State? | INSIGHTS ON PBS HAWAIʻI

Hawaiʻi’s Annexation: Why Knowledge of the History Matters | INSIGHTS ON PBS HAWAIʻI

- The United States Congress issued a formal apology in 1993 via a joint resolution. However, there is still much work to be done to address the damage the overthrow inflicted on the Hawaiian people. ↩︎

- The fascinating story of how the Baibala Hemolele project came about is described in detail in Lyon (2017). ↩︎

- I’m fully aware that these pronunciations would be better represented in IPA, but I’m aiming this entry toward a broader, non-specialist, audience. ↩︎