For this blog entry I decided to do a little French-to-English translating. I thought it might be interesting to present my process and then give a little linguistic commentary. Why French? Well, we’re traveling to Paris soon and I thought it’d be good to brush up on my French, which is not my strongest language (I’d say I’m an advanced speaker but not near-native proficient). For this translation I’ve chosen the song, Little Dolls by Indochine, because I like running to it in the Spring, so I’ve been hearing it a lot lately. If this piece gets any traction I might make this a regular entry and include other languages like Spanish, Latin, Italian, and a variety of different texts other than just pop music, which would be hard for Latin anyway since archeologists have yet to find any cassette-tapes from that era.

Anyhow, the format for this entry is as follows: 1) background on the band, Indochine; 2) a presentation of my own translation and problems I ran into; 3) a comparison with a translation by Google; 4) brief linguistic commentary focused on French first-person plural variation.

Some background.

If you did not experience your coming-of-age in France in the mid-1980s (like I did), then you may not know of the band under consideration here. Indochine was formed 1981 in Paris, basically when electronic pop was gaining momentum. Their most popular early songs are L’aventurier (1982) and 3e sexe (1985), both of which may get their own translation treatment here eventually. Their early work is very reminiscent of early Depeche Mode, probably by no coincidence since they started around the same time. I first discovered Indochine in college via iTunes (that’s what we called it back in those days), when I started studying French. I was looking for some French pop music to listen to and since I was a big DM fan already, Indochine popped up as a recommendation. The first album I listened to was Paradize (2002), which appealed to me because of the religious imagery but also the sexual and sometimes dark lyric material. After that I was pretty much hooked. Although I have yet to see them live, I’d love to do so someday.

The song I discuss below, Little Dolls, is from their 2009 album, Le république des meteors, which I always feel like listening to when spring comes around. You can watch the video for Little Dolls here: Youtube. The album is full of bangers, like Go Rimbaud Go! and Le lac. Side note: a special version of this album includes the band’s cover of Dead or Alive’s famous 1985 track, You spin me round (like a record), which is well worth a listen. Anyhow, I’m not a music critic, so let’s move on to something more language-oriented.

My translation.

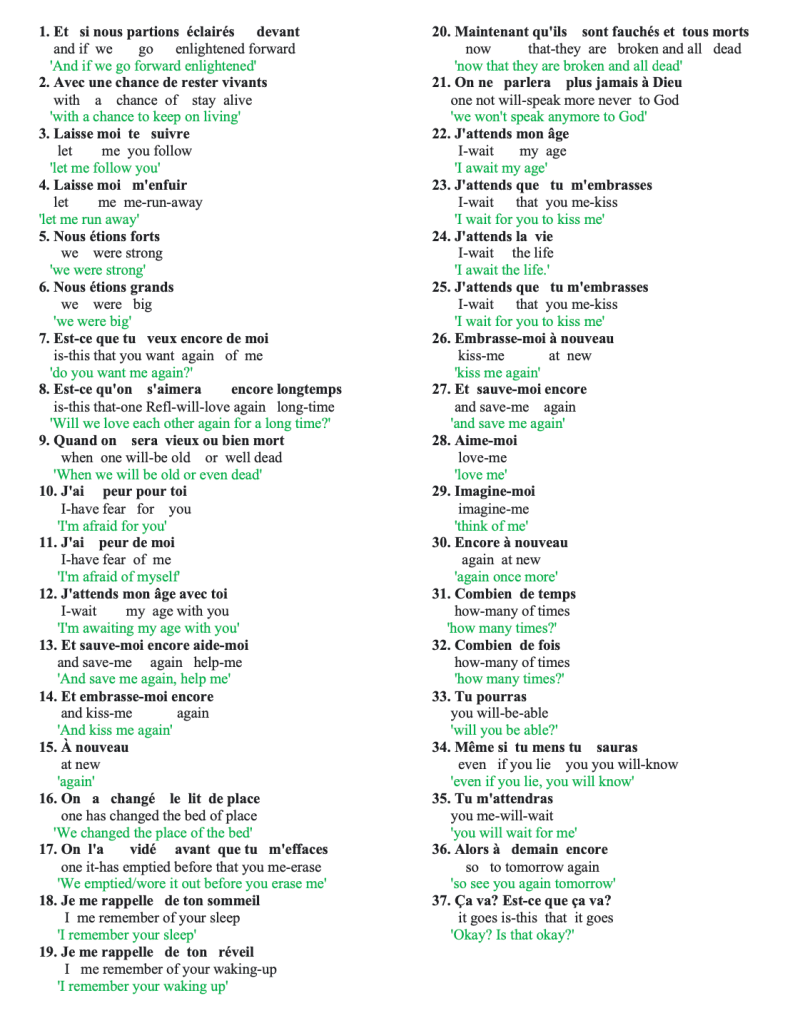

The lyrics were composed Indochine’s lead singer, Nicolas Sirkis, who also wrote the music along with Olivier Gérard and Marc Éliard. As with many pop songs, the language isn’t overly complicated here, but there are some challenges I ran into when rendering it into English. For this translation, I copied the lyrics from online and then went line by line, glossing it literally and afterward putting into somewhat more natural English. I also inserted line numbers so that I can reference them in the discussion. I’m not attempting to reproduce meter here or even make an eloquent translation. Rather, the goal is just to understand the lyrics at a base-level, and maybe learn some new vocabulary. And here it is:

Most lines translated pretty easily, like line 3: Let me follow you. However, there were at least three problems I’d like to present here. First, consider line 12 in (1) below.

(1) J’attends mon âge avec toi.

I-wait my age with you

‘I’m awaiting my age with you.’ (l. 12)

I think I’m missing something idiomatic. The verb attendre is wait or wait for something and âge is like its English cognate. However, what does it mean to await one’s age with someone? It might be something like ‘I’m waiting to grow old with you’, but I’m not sure. Anyhow, this line is repeated several times throughout the song, so if you reading this have a better rendition, I’d love to hear it.

The next issue I ran into occurs in line 16.

(2) On a changé le lit de place.

one has changed the bed of place

‘We changed the place of the bed.’ (l. 16)

The problem here is the phrase le lit de place. According to wordreference.com, changer de place can mean to move, move seats, or trade places with. So, one meaning might be something like ‘we switched places with our bed’, which I think is referring to the frequency of sexual intimacy in this relationship. And the next line also refers to what’s going on in bed.

(3) On l’a vidé avant que tu m’effaces.

one it-has emptied before that you me-erase

‘We emptied/wore it out before you erase me.’ (l. 17)

This verb vider can mean to empty out but it can also mean vacate or even wear out. I’m going to opt for wear out, given the aforementioned frequent sexual relations. This gives us: ‘We wore it out before you erase me,’ the erasing here being the end of the relationship.

Google translation.

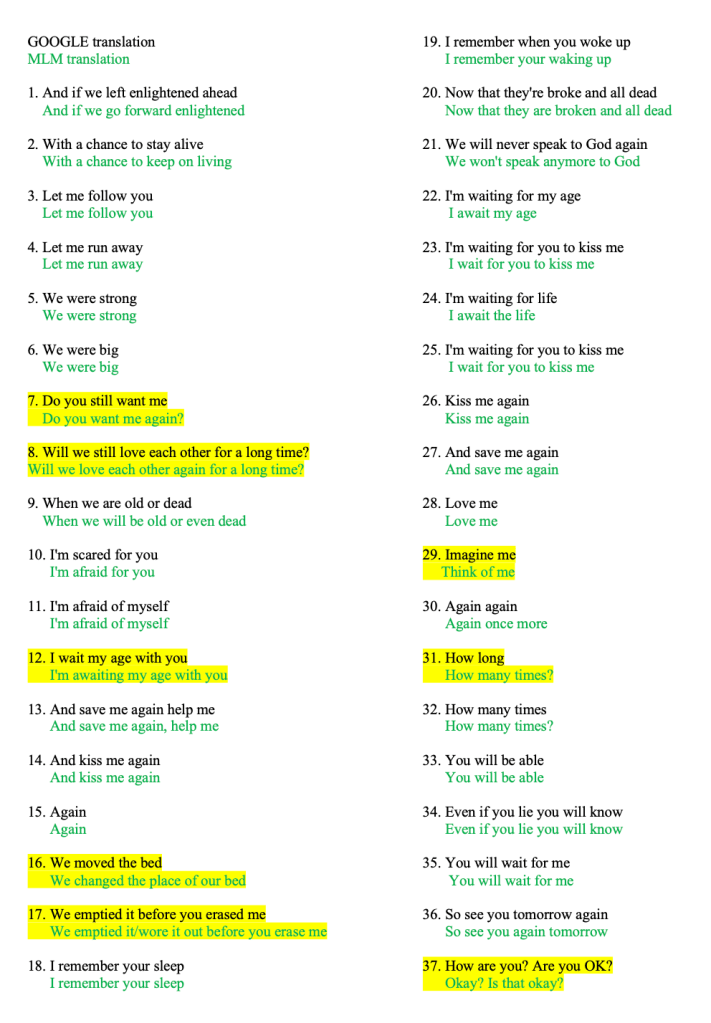

Okay, so as anyone student in French 101 or Spanish 101 or any language 101 course knows, nowadays Google translation can do most of the work for you. However, as anyone who has taught French 101 or Spanish 101, etc., knows, it is not perfect (at least not yet). So, let’s compare with Google came up with and how I translated. You can see below both translations, with Google’s in black text and mine in green.

The good news is that both are similar, so I’m at least as good as Google, and vice versa, but I will make a couple of self-criticisms here. First, in lines 7 and 8, I translated encore as again where still actually makes more sense. So, Google got me there. However, in line 12, we came up with more or less the same rendering (4), which I think still sounds odd.

(4) a. I wait my age with you

b. I’m awaiting my age with you

Furthermore, in line 29, Google translated imaginer with the cognate English imagine while I chose think. I’m not sure which is better here, but think does sound a little more natural. If we compare lines 31 and 32, Google again did a better job in reflecting the French. While I translated both lines the same as ‘how many times’, suggesting repetition of the same word, the French uses two different words for time, temps and fois. Google’s translation reflects this with how long and how many times. And one more difference but not necessarily an improvement on Google’s part is line 37. Notice that in line 36, the speaker is saying goodbye to their interlocutor. In line 37, the French is: Ça va? Est-ce que ça va? Google has this as: How are you? Are you okay? I think that is kind of weird given the parting that was just stated in the previous line. Thus, I rendered it: Okay? Is that okay? The intention here is that the speaker is asking permission to see their lover again the next day, which I think makes more sense, at least on my interpretation of the lyrical content.

Some linguistic observations.

Moving on from translation, let’s do some linguistics. The French used here is standardized, which is not surprising given the lyricist’s background. However, there is one linguistic feature that stands out; i.e., variation in first-person plural expression. This is a well-known phenomenon in French, so I’m not making any novel claims here. To see how this pattern works, consider (5) below, which is my own constructed data, and not from the lyrics.

(5) a. Nous allons au bureau tous les jours.

we go.1P to-the office all the days

b. On va au bureau tous les jours.

one goes to-the office all the days

‘We go to the office every day.’

Notice that both versions of (5) can be interpreted with the subject as we, which is first-person plural. While (5a) has the expected first-person plural subject pronoun nous (equivalent to English we), (5b) has a different pronoun on, derived from the Latin pronoun HŌMO, originally meaning man. This on often receives the first-plural interpretation in (5b), but it can also have a generic reading, according to which the subject would refer to people in general, including the speaker, going to the office every day. For more on French generic on see Maddox (2019:32ff) and references therein.

As mentioned, the nous/on variation in (5) is so well-known that it is even mentioned in prescriptive grammars.1 For example, Judge & Healey (1995:72) refer to the generic use of on as the “real” indefinite and the first-person plural use of on as the “false” indefinite, and proscribe this false use from written language stating that “…only the ‘real’ indefinite on is considered good style in formal written French.” However, as any linguist knows, synchronic variation in the informal, spoken register of a language often indicates historical change. In other words, grammatical patterns and forms we would avoid in writing an essay (under the influence of prescriptivism), are just evidence of a change-in-progress. In English, for example, children are taught in school not to end a sentence with a preposition; i.e., preposition stranding. Consider (6) below.

(6) a. I have a meeting at 9 but I don’t know who I’m meeting with.

b. I have a meeting at 9 but I don’t know with whom I’m meeting.

In (6a), the preposition with is the last word in the sentence, which is considered “incorrect” by your high school English teacher, who would prefer (6b). However, both are perfectly acceptable to any L1 speaker of English and thus grammatical, at least in the way modern descriptive linguists understand it “grammaticality.” In reality, (6b) is much rarer frequency-wise and thus (6a) is likely where the language is heading historically and eventually the no preposition-stranding rule might become obsolete even in the formal register. How does this relate to nous/on variation? In this case, on with first-person plural interpretation is much more frequent than nous. In fact, Fonseca-Greber & Waugh (2003:108) report a frequency of 99% for on versus 1% for nous in their corpus of conversational European French. Thus, speakers almost always opt for on over nous, which means nous is going the way of linguistic dinosaurs, which is okay. Language changes and life…uh…finds a way.

Let’s now apply all this to the Indochine lyrics. Do we see any evidence of nous/on variation in this song? While as a corpus it is admittedly limited in size, we do see some variation in first-person plural subject reference. In fact, in the first line we have nous.

(7) Et si nous partions éclairés devant.

and if we go enlightened forward

‘And if we go forward enlightened.’ (l. 1)

And in line 8, we have on with first-person plural interpretation.

(8) Est-ce qu’on s’aimera encore longtemps

is-this that-one Refl-will-love still long-time

‘Will we still love each other for a long time?’ (l. 8)

Throughout the lyrics, I count a total of eight first-person plural references; three with nous and five with on. Recall that the study mentioned above reported 99% preference for on. How does our little corpus compare? Out of the admittedly few first-person references, five out of eight (62.5%) are with on. This is not as drastic as what was found with conversational French, but it is still consistent in that on is the preferred variant. Thus, the nous/on variation typical of the spoken language is also reflected in pop music lyrics, though the distribution is not identical.

The predominance of on is expected since we’re dealing with informal language (register variation), though the distribution is also conditioned by other social and linguistic variables. For example, the most glaring explanation for the three tokens of nous in lines 1, 5, and 6 could be attributed to meter. While nous partions is three syllables, the parallel form on parte would be two syllables, especially when followed by éclairés with which it would presumably elide. Another linguistic factor could be verb form. Notice that all three instances of nous occur only with present subjunctive verb forms, while on only occurs with the passé composé and the simple future. Verb form is a typical conditioning factor we would take into account if we really wanted to do an in depth sociolinguistic/variationist study of Indochine’s lyrics. Finally, the lyricist might also be taking other factors into account when choosing between the two, including their own prejudices or preferences. Afterall, this is not spontaneous spoken language but rather intentionally composed, written language. It is interesting though that we start out with nous in lines 1, 5, and 6, and then all the other first-person plural references are with on in lines 8, 19, 16, 17, and 21.

So, there you have my translation and commentary on Indochine’s Little Dolls. There were more aspects of the translation I could discuss, but I think this piece is long enough. If you’ve gotten this far, thank you for reading. If you have any corrections or interesting observations on my translation or anything else, please add a comment. Merci pour votre attention!

References

Fonseca-Greber, Bonnie and Linda R. Waugh. 2003. The subject clitics of Conversational European French: Morphologization, grammatical change, and change in progress. In Rafael Núñez-Cedeño, Luis López and Richard Cameron (eds.), A Romance perspective on language knowledge and use: Selected papers from the 31st Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL), Chicago, 19-22 April 2001, p. 99-117. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Maddox, M. 2019. Cycles of agreement: Romance clitics in diachrony. Phd dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagin.

- It is clear that L1 non-linguist speakers are also aware of this variation, given the abundance of YouTube videos by French speakers advising non-native speakers to avoid nous at all costs if you want to sound more native. ↩︎