Recently, while reading research on minoritized and endangered languages (an area I’m new to), I discovered the concept of “positionality.” While this is well known in the fields just mentioned, as well, I assume, by sociolinguists and anthropological linguists, since these are not my fields of specialization, I was unaware of how beneficial this can be for a linguist or any researcher investigating these kinds of languages and their speaking populations. In what follows, I discuss how positionality has been defined in previous work and how researchers like you and I can benefit from writing a Positionality Statement (PS), in which they reflect on how they are situated with respect to their object of study. I also describe the process of writing such a statement and then conclude by presenting a draft of my own positionality statement, for which I welcome feedback from the public.

————————

“Positionality” or “researcher stance” is how the researcher positions themself with respect to their research topic. It is based on the assumption that a researcher’s background and beliefs will affect the type of research they conduct and the conclusions they may draw from it. For example, as a non-indigenous person studying an indigenous language (an outsider), there are certain aspects of my identity and lived experiences that influence my approach to the language, whether I am aware of them or not. To determine one’s positionality, they need to reflect on their identity and how it relates to the object of study. Writing a positionality statement is a way of accomplishing this.

As mentioned, positionality is a concept that’s new to me. I suspect that linguists trained in a more anthropological approach are typically exposed to it in grad school, but for formal syntacticians like me, this is not the case. This is because syntacticians of the generativist persuasion focus on investigating language as an abstract system, which can lead some of us to us separating it from the people who speak the language. In fact, this is a common criticism of syntacticians I have frequently heard from my sociolinguist friends, which I believe does have some validity. In fact, considering our positionality is a good way to avoid this accusation, which is why I recommend my fellow syntacticians consider writing a positionality statement. For one, it is a useful tool to help us reevaluate our motives, especially when investigating minoritized and endangered languages. It raises the question as to why are we doing this work? For prestige? Financial or material compensation? It also forces us to confront more difficult questions such as whether we should be doing this kind of research at all? For example, is it our place (if we’re an outsider) to ask the kinds of questions we’re asking? Are we inviting ourselves into space that is not our own? And who is benefitting from this research other than the two or three academics who may read it when it’s published?

————————

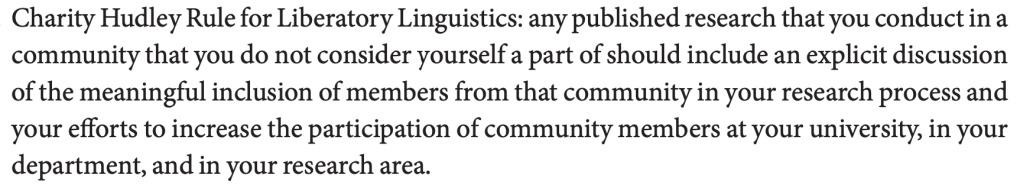

At this point, you may be asking yourself: Should I write a PS? Interestingly, this was the question a young linguist recently asked me when I presented some research on ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) at Université Paris Cité. This individual is investigating a language spoken in Eritrea and Ethopia and, while it is not endangered, the researcher is an outsider to the community, hence the relevance of the question. By way of answering, I referred them to the following rule from Charity Hudley et al (2024:239):

The PS is the perfect document in which to carry out this “explicit discussion.”

————————

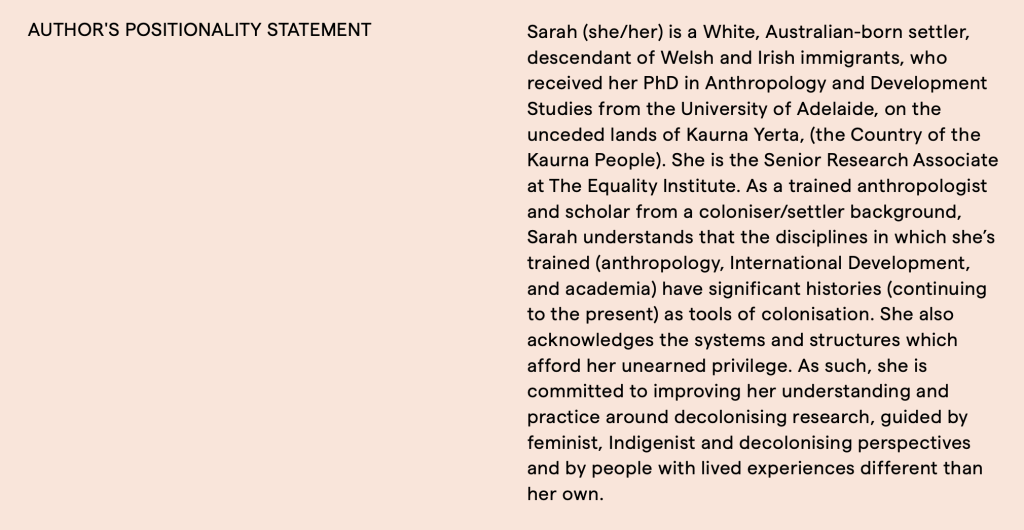

So how does one go about writing a Positionality Statement? A good place to start is by reading Sarah Homan’s (The Equality Institute) very concise blog post, “Why positioning identity matters in decolonising research and knowledge: How to write a ‘positionality statement’. After a brief explanation of positionality and the positionality statement, Homan offers four groups of questions to guide the writing process, which I reproduce in adapted form below.

QUESTIONS FROM HOMAN (2023) TO GUIDE THE WRITING OF A POSITIONALITY STATEMENT

1. What are my different social identities and how significant is each identity to my work? Social identities can include, but are not limited to, gender, race, nationality, sexual orientation, age, social class, religion, dis/ability and so on.

2. What experiences do I have? How have they shaped who I am professionally?

3. In what discipline did I train? What role did my discipline play in establishing dominant worldviews? What role do I play in this work? In what ways do I challenge or divest from some of these practices? Why or why not?

4. What are my values and what do I hope to achieve through my work?

———————–

Another great resource, especially for my fellow syntacticians, is Gibson et al (2024), which addresses our field specifically and approaches to decolonizing syntax. These authors also provide a series of questions that can guide the PS writing process. For research methodology specifically, see pages 233 to 234.

Given my outsider status as a researcher on ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, I have composed by own PS which I present here as a draft. As this is a work in progress, I’m happy to hear constructive feedback, especially from those with more expertise in this area than myself.

References

Charity Hudley, Anne H., Mallinson, Christine, and Bucholtz, Mary (2024). Decolonizing Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gibson, Hannah, Jerro, Kyle, Namboodiripad, Savithry, and Riedel, Kristina (2024). Towards a Decolonial Syntax: Research, Teaching, Publishing. In Charity Hudley et al (eds), Decolonizing Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 219-243.

Homan, Sarah. (2023, February 15). Why positioning identity matters in decolonising research and knowledge production: How to write a ʻpositionality statement.ʻ The Equality Institute. https://www.equalityinstitute.org/blog/how-to-write-a-positionality-statement

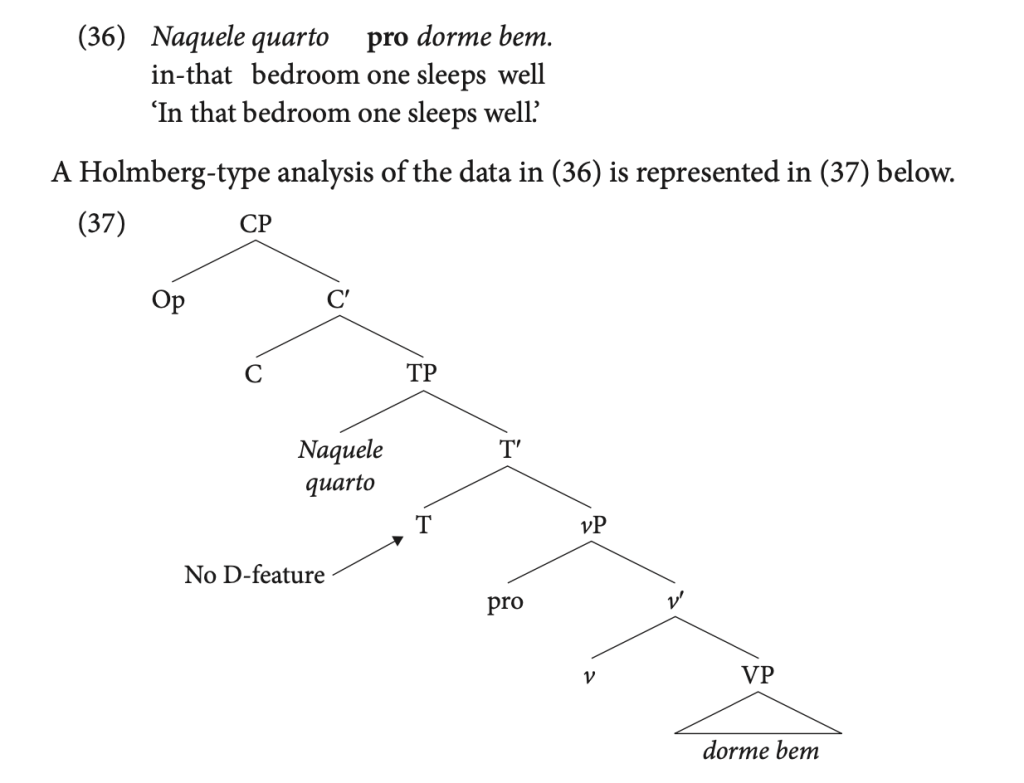

Maddox, M. (2018). Licensing conditions on null generic subjects in Spanish. In Repetti, Lori, and Ordóñez, Francisco (eds), Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 14: Selected papers from the 46th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL), Stony Brook, NY. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 185-199.

Other work on positionality:

Bourke, Brian (2014). Positionality: Reflecting on the Research Process. The Qualitative Report 19:1-9.

Holmes, Andrew Gary Darwin (2020). Researcher Positionality: A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research – A New Researcher Guide. Shanlax International Journal of Education 8:1-10.

Lin, Angel (2015). Researcher Positionality. In Hult, Francis M., and Cassels Johnson, David (eds), Research Methods in Language Policy and Planning: A Practice Guide. London: Routledge, 21-32.